Sports-related concussions that cause mild traumatic brain injury are receiving much attention worldwide, due to the potential risk of developing long-term neurological issues including behavioural and cognitive changes. There may also be risk of neurodegenerative disease. For example, repetitive head injuries have been associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which can only be diagnosed post-mortem.

The most significant problem in managing concussion, especially for youth, is deciding when it is safe for an athlete to resume sports. Most organized sports teams, from school teams through to professionals, use return-to-play (RTP) protocols to determine when it is safe for an athlete who has suffered a concussion to resume physical activities. In addition to the number of days since injury, RTP protocols are based on clinical examination and symptom reports, but not objective measurements of brain injury and recovery.

A new digital headset designed to measure alterations in brain function could aid in this decision. Researchers from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) conducted a study using cranial accelerometry to measure micromovements of the head following cardiac contraction (referred to as the “HeadPulse”). Writing in JAMA Network Open, the team reports that serial measurements of the HeadPulse biometric reveal characteristic changes after concussions, and that these changes continued an average of 14 days longer than reported concussion symptoms.

Led by Cathra Halabi, the researchers evaluated 43 concussed and 59 control athletes from the Adelaide Football League (AFL) in Australia, including 69 males and 32 females aged between 19 and 31 years. The participants played the highest level of amateur Australian rules football, a distinct contact and collision sport in which opposing un-helmeted teams score by running, kicking or punching a ball toward goalposts at either end of a large field. Tackling or jumping on an opponent are common manoeuvres. AFL team members who suffer a concussion are not allowed to resume sports activities for at least 12 days.

The researchers conducted the study in two phases over two seasons, first in 2021 to confirm feasibility and refine methodology, and then in 2022 to validate findings and associate physical activity with brain function measurement patterns. Research coordinators attended games and were alerted to players with a concussion.

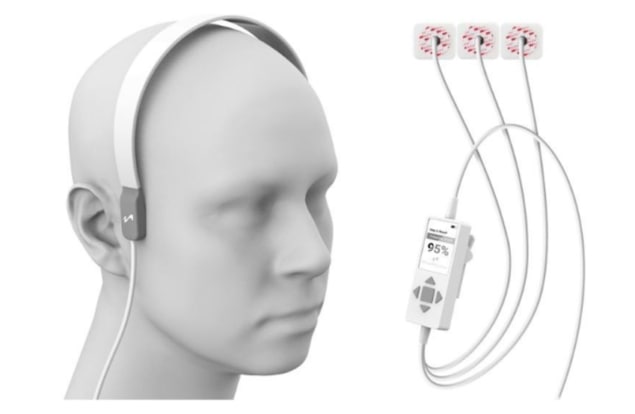

The coordinators performed brain function measurements within an hour of a player’s concussion, using a prototype headset under commercial development by medical technology company MindRhythm. They subsequently travelled to these individuals’ homes every one to three days over the next 30 days to obtain additional recordings. Participants completed a neurobehavioural symptom inventory (NSI) with each recording.

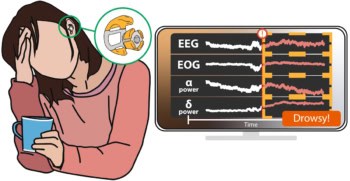

The HeadPulse, a unique physical biomarker, is measured by applying a sophisticated sensor to the patient’s head that detects normal and abnormal forces pulsing through the brain. The HeadPulse effectively indicates any deviation from what is considered healthy and identifies changes in how forces travel through the brain. Highly sensitive cranial accelerometers measure minute pulsations produced by each heartbeat caused by the force of the cardiac cycle. The data are transmitted to a smartphone, with the entire process taking less than 180 s.

During the first study phase, the researchers acquired and analysed 137 recordings of 12 concussions in male athletes only. In the second phase, they utilized a second-generation prototype device that resolved some excess body motion problems to acquire 276 recordings of 29 concussions in both males and females. They also acquired a 262 recordings from 58 control participants.

Twenty-six of the 32 concussed individuals met the biometric abnormality threshold within the first seven days. HeadPulse analysis detected 9% of concussions on day 0, 50% by day 2, and 90% by day 14. Of the 32 participants, 26 had NSI scores that returned to zero within 30 days. In those with symptoms lasting less than one month, half returned to a zero NSI score by day 7. However, compared with resolution of symptoms, only 57% of participants demonstrated biometric resolution by day 30, with 50% achieving this by day 21 – 14 days later than the NSI improvement.

“We found a mismatch between reported symptoms and changes in biometrics recorded by the device,” says Halabi. “This raises concern about relying on symptoms for RTP decisions. Delays could be recommended for those symptom-free athletes if HeadPulse abnormalities persist.”

“Speculative causes of sports-related concussion (SRC) HeadPulse signal changes include alterations in brain parenchymal mechanical resonance (stiffer brain) induced by concussive injury, modulated by vascular response,” the team writes. “Heart rate harmonics are central to head pulse derivation, and SRC-related autonomic dysfunction may contribute to HeadPulse changes.”

For concussions, the eyes are windows to the brain

The researchers advise that the association between HeadPulse and activity, including exercise, requires additional investigation. They are currently conducting a study at UCSF, in collaboration with the University of California Berkeley, to determine whether student and non-student civilian athletes can self-administer the device. The team is also collecting additional information about clinical features of concussion and activity levels to help characterize the HeadPulse.

- UCSF researchers will present the results of a recently completed observational clinical trial (EPISODE) evaluating the use of HeadPulse for ischemic stroke detection at the forthcoming 2023 American College of Emergency Physicians (AECP) Scientific Assembly, held in Philadelphia in October.