The most likely source of the strongest shallow “moonquake” ever recorded is less than 60 km from the lunar south pole and within many of the proposed landing zones for NASA’s forthcoming Artemis III mission. According to researchers at the US National Air and Space Museum’s Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, who identified the source by re-analysing data from lunar seismometers set up by Apollo astronauts over 50 years ago, moonquakes of this type originate from a fault or thrust that causes the lunar surface to contract. Because the seismic shaking from such an event could trigger landslides, the researchers warn that future lunar astronauts – including those aboard Artemis III, which is currently scheduled to launch sometime after September 2026 – will need to be careful where they land.

Over the last few hundred million years, the Moon has been shrinking as its core gradually cools. This shrinking led to global stresses that produced so-called contractional (or thrust) tectonic deformations in regions where sections of crust push against each other. Such deformations are known as lobate thrust fault scarps, and they resemble long, irregularly-curving wrinkles tens of metres high. Like on Earth, these lunar fault scarps are home to seismic activity. Because they are among the youngest landforms on the Moon, some of the small thrust faults that produced them are likely still active today.

Much of our knowledge of the Moon’s recent seismic activity comes from the Apollo Passive Seismic Experiment (APSE). This consisted of four seismometers placed at the Apollo 12, 14, 15 and 16 landing sites between 1969 and 1972. These seismometers operated until 1977 and recorded a total of 28 shallow moonquakes (SMQs) with equivalent magnitudes ranging from 1.5 to about 5.

Though moonquakes resemble earthquakes in some ways, they can last much longer – up to several hours compared to a few seconds or minutes. Indeed, the APSE recorded one magnitude 5 SMQ that lasted a whole afternoon.

Tracing a moonquake to its source

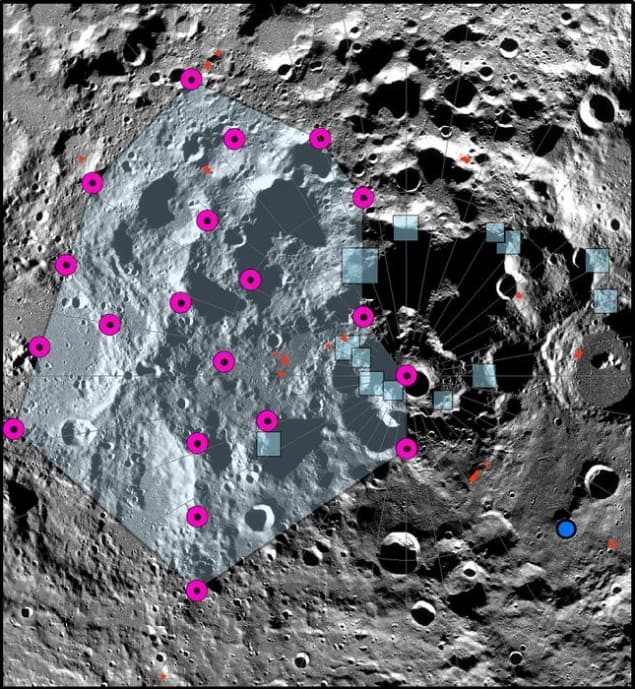

In 2019, a team led by geophysicist Thomas Watters reanalysed this long-duration moonquake, searching for a likely source among the young contractional faults photographed by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera’s Narrow Angle Camera. In the latest work, members of the same team focus on a small cluster of faults near the lunar south pole, including one that falls within the so-called de Gerlache Rim2 Artemis III candidate landing region. This fault, they say, may have been the source of one the strongest SMQs recorded by the APSE, with an estimated magnitude of 5–5.6.

The team’s modelling suggests that this SMQ could have produced strong to moderate ground shaking over a distance of least 40 km, with moderate to light shaking likely over even larger areas. What is more, models of slope stability predict that steep slopes in the Shackleton crater (located near the lunar south pole) may be susceptible to landslides from even light seismic shaking – especially since the lunar soil, or regolith, in this region is loosely consolidated and contains dry gravel and dust.

Japan’s lunar lander falls head over heels for the Moon

Seismic events from active thrust faults should be taken into account

Based on these findings, the researchers argue that the possibility of seismic events from active thrust faults should be taken into account when preparing future lunar missions and locating permanent outposts. In their view, these events are a potential hazard for future robotic missions as well as human explorers. “We hope to sound a cautionary note: that the Moon is a seismically active body and that there is a potential hazard to long-term settlements, if they are located too close to a young fault,” Watters tells Physics World.

The researchers are now examining the stability of slopes in permanently shadowed regions in more detail. “We also plan to look for evidence of recent landslides where they are predicted by our model,” Watters says.

The study is published in The Planetary Science Journal.