After doing a PhD and postdoc in quantum technology, in the UK, Joanna Zajac spent three years in industry before returning to fundamental research. She now works as a quantum scientist at Brookhaven National Laboratory. So how do academia and industry differ and which one is right for you?

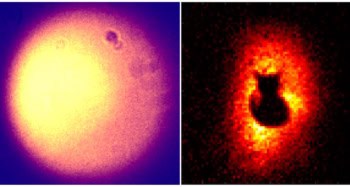

The fundamental conundrum for junior scientists after graduating is whether to move into industry or continue in academia. I have worked on both sides of this divide. After completing my Master’s degree in physics at Southampton University, I went to Cardiff University to do a PhD on novel types of vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers. I then did a postdoc at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, and at the University of St Andrews, where I worked on single-photon laser diodes and how they can be applied to quantum information technologies.

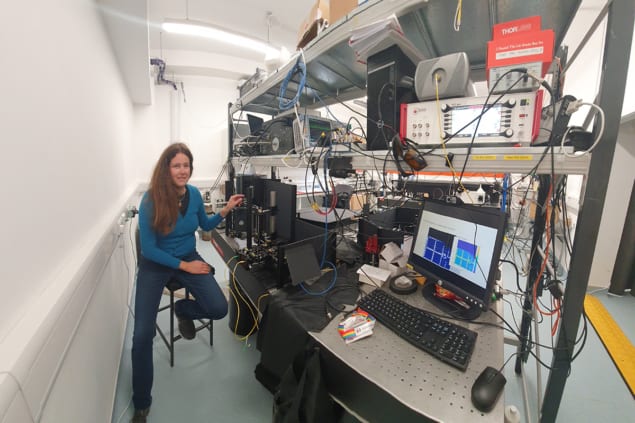

In 2017 I switched to industry and became a quantitative analyst at Moody’s Analytics, a financial-services and risk-assessment company that does research and creates tools for corporate clients. While there, I used my strong mathematical and programming skills to do research in applied finance. After working in industry for three years, I then went back to fundamental science, becoming a senior researcher in quantum computing at the University of Oxford. Last year I moved to Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US, where I currently work as a quantum scientist.

So what are the main differences between academia and industry? In my experience they centre on four major aspects of working life: preferred working style, management, balance between work and family life, and the actual tasks involved in a job. Any career decision is ultimately your own, but I hope my perspective helps you to make a well-informed choice for your career.

The main differences between academia and industry include preferred working style, management, balance between work and family, and the actual tasks involved in the job

Preferred style of work: individual or teamwork

If you are more team-oriented, industry might be a better choice for you. It depends on the company culture, but in industry you are likely to be part of a team collaborating on a project. If you are involved in interdisciplinary projects, as I was, you will be working with colleagues who have expertise in a broad range of areas.

During my time in finance, it was a bare-minimum requirement to have an economist, a physicist and programmers on a team when tackling complex problems in modelling financial markets. A huge benefit for me was that I learned from all these professionals with different backgrounds, who each brought unique skills to the table. For instance, I learned how to do risk modelling while working in teams like this.

In academia, in contrast, group dynamics vary depending on the principal investigator, but in physics and maths there is usually a strong emphasis on individual work. This means you are driving your own research, hopefully given the space and resources you need to grow. I did my PhD and postdoc very much independently and my achievements reflect my determination and hard work. However, this emphasis on individual work creates a highly competitive environment, which I do not think is beneficial for the development of young researchers.

I feel that close collaborations and interactions with colleagues are hugely beneficial, especially during the early stages of your career. That’s when it’s important to learn not only practical knowledge but also soft skills like communication and management. Consequently, the higher level of guidance and feedback that you get in industry makes it easier for you to learn and improve on the job.

Management

Another feature of industry is that there is more structure and risk mitigation, with product managers ensuring that solutions are delivered to clients on schedule. In my case, I was responsible for developing and implementing financial modelling tools, among other tasks. My projects had specific resources assigned to them and concrete deadlines that needed to be met. Although the work was clearly structured, it was not always easy, and there were times when extended team efforts were required.

Working in academia tends to be much more ad-hoc, with flexibility to choose what you work on and when. This arrangement can be great, especially for people with strong focus and time-management skills, and it suits me. However, it might not be ideal for everyone, and it takes time to adapt. You might find yourself overwhelmed by passing time with scarce results.

Although some risks are considered and mitigation measures taken in academic research, this is not done as rigorously as in industry. The chances of bottlenecks, especially for collaborative projects, are therefore higher in academia.

Balance of work and family life

One big benefit of industry is that the working environment is more accommodating for employees with families than it is in academia. With companies offering generous benefits to attract top talent, it is easier to find the stability and resources required to support family life. There also tends to be more social interaction with colleagues from various backgrounds who often happily share their own experiences and advice. More generally, there is usually much more going on outside of work too, such as charity events or after-work get-togethers, all of which contribute to a healthy work environment.

Academia lags behind when it comes to supporting employees with families. There are various initiatives aiming to address this. Athena Swan, for example, is a charter and accreditation scheme that makes recommendations on how academic departments can improve gender equality and gives awards to recognize and encourage efforts in this area.

I was a member of the Athena Swan committee at both Heriot-Watt and Oxford, and our efforts were aimed at introducing more benefits for working parents, such as adopting shared parental leave. However, in my opinion, these initiatives do not reach far enough and are slow to keep up with evolving needs.

This is especially visible in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) departments where it is very rare to hear of a colleague taking maternity leave. I believe that the limited support available for parents and the prevalence of short-term contracts in academia contribute to the low retention rate of female academics in STEM fields.

Tasks involved

The final major point to consider when deciding whether to move into industry or stay in academia is the actual work you will be doing. Industry is product-oriented, so you will see your idea develop from the whiteboard through to implementation, and even receive feedback from users. While working at Moody’s Analytics, for example, I was involved in projects developing client-oriented software solutions for use by financial institutions. My colleagues and I did write reports and papers about our research, just as we would in academia, but these documents were for internal purposes only to protect the company’s intellectual property.

This product-development cycle is rarely present in academia, where the projects are usually on prototype-stage ideas or even completely blue-skies research. The focus on very detailed tasks can certainly be intellectually stimulating, but it can also leave you longing to work on something more applied and immediately useful. Having said that, current graduates have much broader career options compared with what was available to me and my peers when I graduated almost 15 years ago. This is because quantum research has become much more mature and product-driven in recent years.

In the end, the choice of which path to take depends on what type of work and professional environment you will personally find satisfying. What is most important is that you make yourself aware of these differences, so you can find a job and workplace that is right for you.